I was recently asked how I, as a staff engineer, work with and upskill other developers on my team. It was a great question, and I thought I'd write down a longer form version of the answer I gave.

A core part of staff engineer's role is to grow the team. A staff engineer who doesn't up-level other engineers is a bottleneck. Staffs look to accelerate their team and their growth, so training and upskilling is incredibly important. It is also not really talked about, with most staffs picking up the skills haphazardly. Is there a better way to do it?

Well, if you want to help someone improve, the first step is to figure out their level. There is no one-size-fits-all all progression strategy, and anything you do must factor in their levels and skills. Figuring this out can be tricky, given that skills in software development can seem ephemeral and vague. This is where a model comes in handy, and this is why I use the Dreyfus skill model to figure out where they are and how to get them to the next stage.

Dreyfus skill acquisition model

The Drefus skill acquisition model is a way to categorise where someone is in their journey from beginner to expert in a given skill. It has 5 stages (with a 6th for special people), those stages are:

- Beginner: Just starting and only learning the fundamentals

- Advanced beginner: Can solve simple problems, understands rules and where to apply them

- Competent: Can solve most problems, but is rigid and makes mistakes

- Proficient: Solves most problems, spots problems before they emerge

- Expert: Able to solve any problem in their space in an intuitive way

- Master (special): They challenge the existing paradigm and discover new ways of doing things

This model is actually a spectrum, with people moving from one side to another rather than in discrete jumps from stage to stage. On the left-most, they are consciously thinking through every step they make, on the right-most most they are making intuitive decisions and seem to skip steps yet end up at the right, or optimal, answer. It is also only a model and is not reality, but it is considered incredibly effective in many educational fields, so, ya know, it's been vetted. Good enough for me!

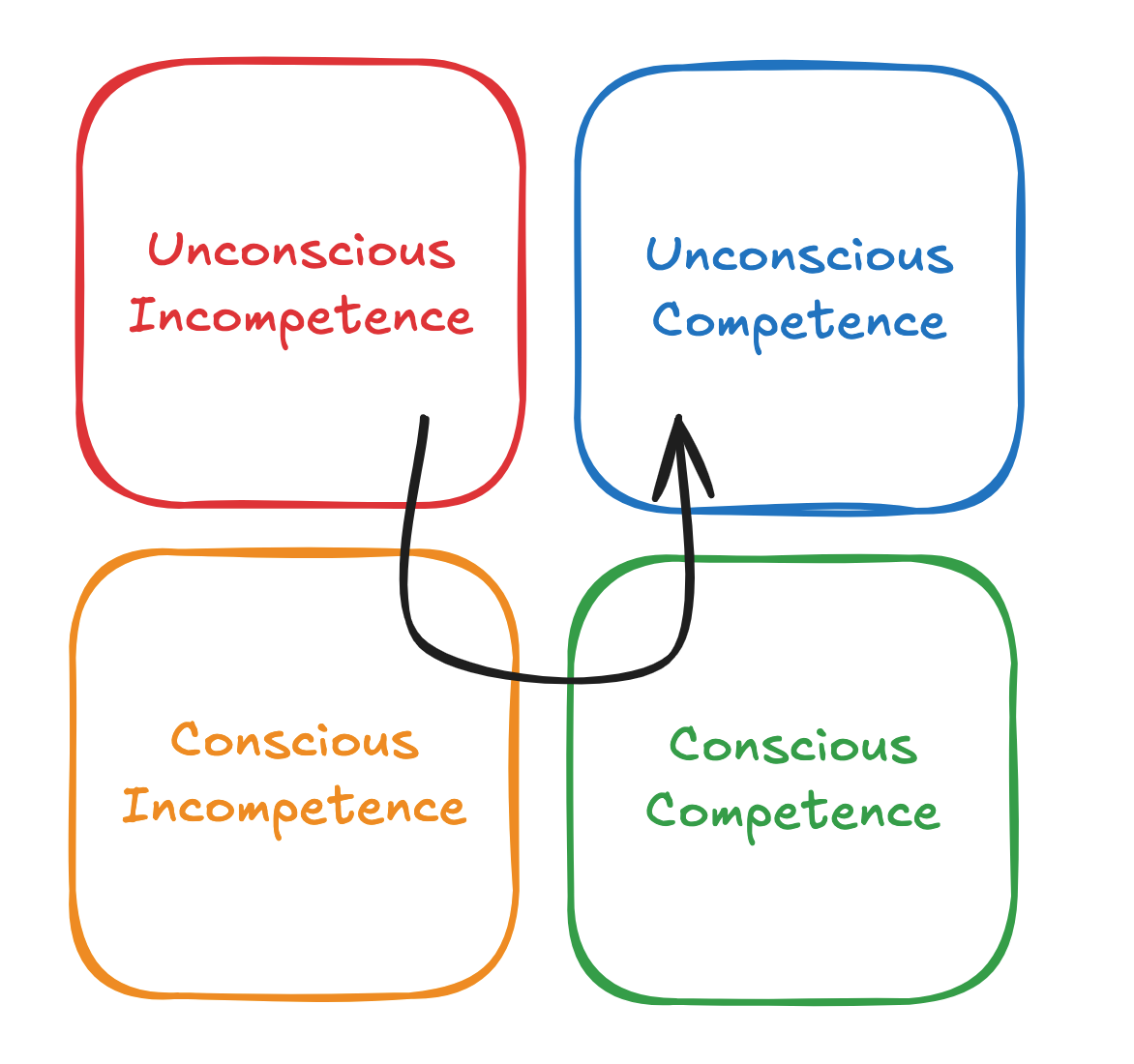

This model also aligns with the Four Stages of Competence model. In this model we progress through four stages when gaining skills. We start unaware of our incompetence and finish at competent without conscious effort, becoming intuitive in the problem space.

People in the final stage are able to make large intuitive leaps, often seemingly skipping steps while reaching an optimal conclusion.

Conscious: A -> B -> C -> D Intuitive: A -> K

This makes sense. To learn something you must be conscious of it, but as time goes on consciousness becomes the bottleneck, and our brain forms new internal structures to spot patterns and speed up the process. This then allows for new levels of conscious thinking, leading to new unconscious patterns. It's a cycle, and being aware of it fast-tracks progression.

What makes these models especially effective is how they factor in the way our brain acquires skills over time.

How we learn

The brain works through reinforcement learning. Deliberate actions lead to outcomes, which our logical or emotional systems reinforce as good or bad. After a while our brain spots patterns and we gain unconscious processes that quickly evaluate our options and present an answer to the conscious mind. This can manifest as a sudden thought or even an emotional response (e.g. "This function feels iffy"). Lower layers are concrete while higher layers are more abstract. As time goes on these processes will begin to layer, meaning that we're able to work at higher layers of abstraction over time.

A key point here, practice is everything. You can't learn how to write software by reading a book. Sure, it will give you ideas, but ideas without practice are disconnected from actual experience and thus have no connection to lived reality. (I'm not saying don't read, dear god don't think that, reading is super important! Just be sure to practice as well.)

A concrete example is a skill we've all learned and perform intuitively, though most of us don't remember learning it. Walking. We do not know how to walk when we're born and must learn how to move through conscious trial and error (walking is actually really difficult; we're technically falling forward in a controlled way). After a while we no longer need to think about it; we just do it.

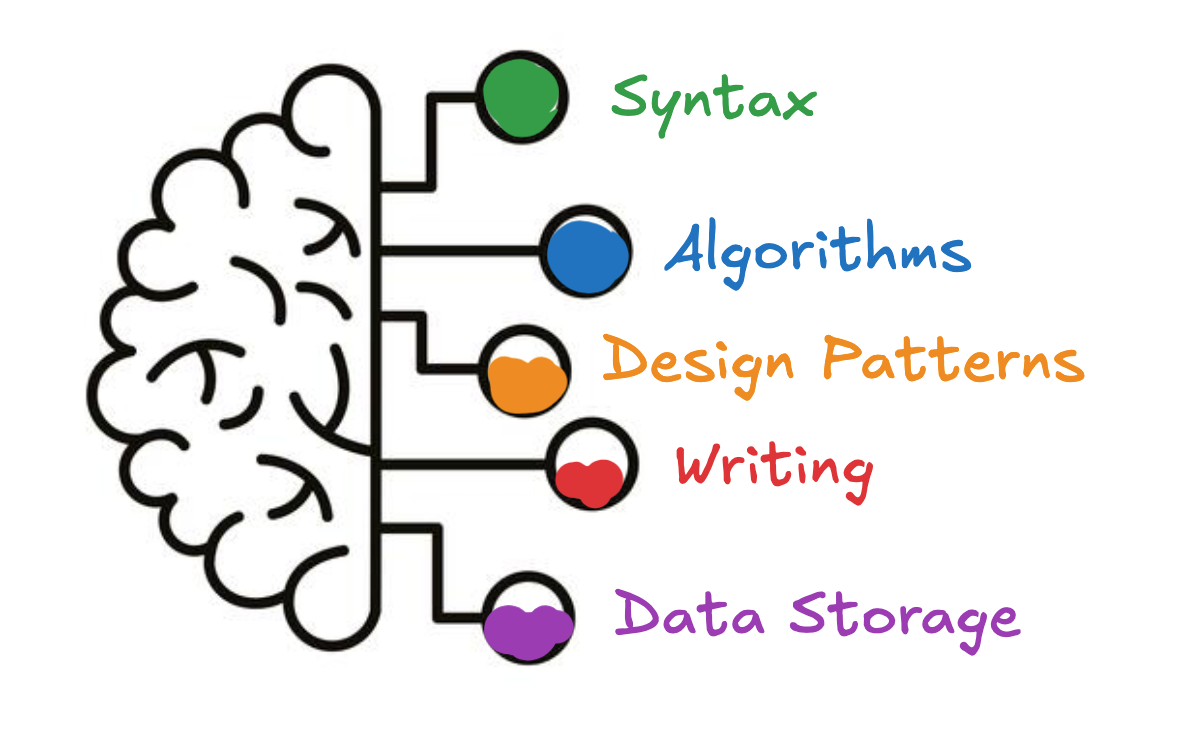

The same is true for coding. At the beginning you have to consciously think about every keystroke and how it solves the current problem. Once you've mastered this it becomes an automatic process; your brain directly translates intent into code. From there you move up into thinking about structure, how to fit code together (potentially into classes) to solve a problem. As you gain more experience you stop consciously focusing on local structure and instead think about business problems from a design/architecture perspective, weighing up their pros and cons before making a choice.

From this it's clear that lower layers enable higher layers, but there's also another aspect: time frames expand as you grow.

Skill acquisition time-frames

The time frames for gaining a skill grow as the skill gets more abstract and the feedback loops become longer.

The feedback loop for syntax is relatively short: you write code, run it (or your IDE highlights the issue) and rapidly encounter errors before immediately addressing them (or you get stuck and get frustrated before asking for help). The distance between action and result is short. You soon gain an intuitive sense of what syntax to use and won't need to consciously think about it; your brain will just do it for you.

Conversely, the feedback loop for projects and systems is much larger. At the beginning you won't see the problems with your design until later in the project or after it's been running in production for a while and you're finding it difficult to maintain or change. This is why retrospectives and reflection are so important. They let us review what we've done, figure out what worked and what didn't, and give our brain the feedback it needs (both informational and emotional) to build these intuitive units.

The big picture

We often hear that everyone should understand the big picture (as critiqued in a solid article on the Dreyfus model in software development), but that assumes that understanding the "big picture" will guide people towards optimal decisions at their level. The Dreyfus model states that this isn't the case, as the "big picture", i.e. the next useful abstraction level, is skill dependent.

Let's take beginners, they can't follow abstract big picture concepts like "clean code", "SOLID principles" or "increased revenue", because they don't have a mental framework to process these concepts. They don't have the information or knowledge to bridge the gap, there are just too many unknowns and missing skills. Their big picture must be much smaller and closer to their level in order to be effective. That's why I'll discuss the appropriate big picture for each stage.

So given all that, how:

- Does each level manifest in software development?

- How big should the big picture be?

- Can we factor this in when enabling these developers?

- Do we optimise the feedback loops for progression?

Stages:

Before we dive in, I would like to state that I'm going to model each stage for a generic software developer. The diversity of skills across software development is large, but there are commonalities. You will probably have your own competencies and skills that are important to your org that aren't mentioned here, but they can easily be fitted in. First, figure out where that skill is on the spectrum, then ask yourself if they have the foundational skills required for that skill, starting at the bottom and working your way up.

Now, onto the stages.

1. Beginner:

A beginner software developer is new to software development. They are at the syntax and language features stage of software development and are learning how to write code and solve a problem at the same time. They will be slow, make lots of syntax errors and will have difficulty when their code isn't doing what they expect it to do.

We often call these developers "juniors".

Their big picture is the line of code they are currently writing and maybe the immediate problem they are trying to solve; anything beyond that is too much for them. This should be expected, as they are doing two things once, problem solving and learning syntax. This requires a lot of cognitive capacity and conscious effort, leaving no room for anything else.

Enabling Beginners should work on simple tasks. They do well with golden examples of how to do things, e.g. code snippets for production code and tests. They will use those as scaffolding for their solutions, which will accelerate their development and productivity.

Growing Patience is key when working with beginners, they should be given simple procedural tasks that let them learn syntax, basic structures and how to solve problems. They are not there to be prolific; they are there to learn. Iteration, trial and error, pairing and coaching are essential at this stage. Once syntax is learned and is no longer a purely conscious activity (i.e. they don't need to think about proper syntax, they just know) then they are ready for the next stage.

The feedback loops at this stage are so small and clear, so little needs to be said.

2. Advanced beginner

An advanced beginner software engineer knows how to code. They have a solid grasp of the fundamentals, can write code and solve simple problems. They rely on rules and patterns and struggle when they encounter new and unfamiliar situations.

We often call these developers "software engineers".

At this stage they are probably aware of design patterns and architecture but have not practiced with them and are not sure of which pattern to use in a given situation. They typically know what they don't know, which makes it easier to chart a path forward for them.

Their big picture is the immediate business problem they are solving, such as a bug or a part of a feature. They are aware of software design concepts but they lack an understanding of the underlying principles and thus make procedural and suboptimal design decisions.

Enabling Advanced beginners can work on slightly more abstract problems. Their tasks can be a little vaguer, focusing on the problem to solve with a few technical details, then it's up to them to figure out a way to do it. Once the scope of the problem begins to span multiple classes and boundaries, they will begin to struggle, so keep a watch out for an explosion in problem complexity.

Growing Growing them can involve code reviews and then a pairing session to show them different solutions. Training in and practicing with design patterns and various technologies is essential here, as you want these ideas to become known and settle in their brain, much like syntax, becoming options they can consciously think through to solve spotted problems. Once they are able to break a user story (desired behaviour) into technical tasks and execute, then they are progressing to competent.

The feedback loops are larger, but still small enough for the dev to get useful feedback. Reviewing and pairing are two great ways to speed up this feedback loop, as it tightens the loops and gives strong feedback signals.

2.1 Anti-pattern: The Expert Beginner

During the journey from advanced beginner to competent devs can get derailed and stuck in a toxic mutated state called the "Expert Beginner". An expert beginner is someone who has succeeded with their chosen selection of patterns and techniques and has thus decided that they are now an expert and can build anything. Abstract concepts are considered "philosophical faff" and rejected, while anything they practice is required knowledge and the "right way™" to do things. Expert beginners act like they understand the big picture but are really just shuffling their known solutions around until it looks like they work.

A lot more has been written about this so I won't belabour this one. Erik Dietrich coined the term, I believe, and wrote the first article on it, so I'd highly recommend you give it a read.

You can spot expert beginners by how overly confident they are. Actual experts expect nuance and change over time; their suggestions are only right in their current context. Expert beginners on the other hand are very prescriptive and will reject any ideas you present that are beyond their scope.

The best way to prevent or move past this stage is to read about higher-level concepts around design and structure. Practice new patterns and ideas and embrace the understanding that there is a lot you don't know and that is ok. Humility, as ever, is key.

3. Competent

Competent developers are starting to get the hang of things. Given a project specification they are able to discuss the details and figure out a plan, turn that plan into steps and then execute on it. They know how to write code, how to select technologies and tools and how to connect them altogether to solve a problem. They will have more of an emotional investment in the project and its outcome as they are the designer.

This is where the title of "senior developer" typically gets used.

However, competent developers still proceed by conscious analysis, evaluation, and deliberate rule-following. They have little experience or intuition to lean on, so instead they trust the plan. This can lead to problems in vague or evolving spaces, as once they create a plan they will stick to it even when circumstances change. E.g. say the spec changes, they discover edge cases that complicate the solution, discover a blocker to the problem, or even a simpler way of solving the core problem. Rather than re-evaluate the plan, they will work around the emergent issues and work a solution into the current plan, leading to systems built for one problem but solving another. This makes the resulting software harder to understand and change.

Their big picture is the big picture of the project and the problem it's solving, mixed with principles of design and maintainability. They want to build the best thing they can and are attempting to follow some abstract principles, but they are doing so in a rigid and logical way and don't really have a sense of which patterns, architecture or designs will get them there.

Enabling Competent developers can work on full-blown projects from start to finish. They are able to work with product partners to figure out the features and turn those into tasks. However, the more complicated the problem, the more likely it is that their plan will be unable to handle changing needs. At this stage, you should offer support and work with them to review the plan and, leaning on your experience, look for potential problems, translating your intuition into principles and suggested actions. Show them the different options they have and then work with them through the project to process any new discoveries, re-evaluating the plan rather than hammering in changes. Be sure to give them space, competent devs don't need their hands held, they should be allowed to work without constant check-ins.

Feedback loops The feedback loops here are much larger, so progression can slow down. If you want to accelerate gaining intuition, then they must feel the consequences of their decisions. Let them make a mistake and live it for a while (provided it's not costly and actively damaging the business) before helping them fix it. Experience is a great teacher after all, and the emotional pain of losing momentum will give their brain direct and actionable feedback.

4. Proficient

Proficient devs can take a spec, formulate a plan and then intuitively spot problems with their plan before execution. They know what works and what doesn't when building their solution. They can handle changing environments and will incorporate new information on the fly and adapt their plan if possible. Proficient engineers are not just good at software development; they are also excellent communicators. They ask the right questions, often intuitively spotting gaps in the spec, and can express their ideas in multiple ways, tailoring their message to the recipients.

Saying that, while the problems are now intuitively spotted, the solutions are not. They must still consciously think through the solutions to the problem and will apply rule-based thinking to reach a solution. E.g. they can look at how a service is designed and spot that the resulting system will be difficult to test or debug, at which point they'll look for potential solutions and weigh up the pros and cons iteratively, choosing the "best". Or they'll look at the patterns in an existing piece of code and spot that they're getting in the way of required change and need to be refactored. Into what they don't know yet, but they incline what's wrong.

This is where developers are traditionally considered "staff". They can read spec docs, propose plans (both their own and others), and spot issues, suggesting potential solutions after a little bit of thought. They can communicate clearly and are able to work with non-technical people to solve problems.

Their big picture is the maintainability of their systems and how they interact with the rest of the system to address business problems. They will uncover new problems and should be allowed to do so. This is where the business can start to be vague and just give abstract requirements that the eng can turn into a plan, they'll figure it out.

Enabling proficient devs is easy. They'll know what they know and what they don't know. Ensure they have a support network for reviewing their proposed solutions, as that's the area where they lack intuition. Like competent devs, they don't need a lot of management; at this stage they should manage themselves. They don't have an intuitive sense of what solutions will work yet, so it's best to let them try their preferred proposed solutions and see where they go, rather than telling them the "correct" solution (unless they're stuck or ask for your direct feedback). Encourage them to let go of rules and procedures (e.g. frameworks for choosing a storage mechanism) and instead trust their intuition and see where it goes.

Feedback loops here can actually be shorter than competent, as they have built an intuitive sense of the problems, but only if they have fellow proficients to offer suggestions and grow their intuitive skills, or experts to suggest paths no one else has. Having either or both readily available can be rare. To fast-track their development, let them explore potential solutions, prototyping a few of them and then have a small retrospective on the results. Let them lead, highlighting what worked and what didn't. If there is an insight they're missing share it, but don't dominate the conversation.

5. Expert

An expert engineer is almost a purely intuitive creature. They are a continuous learning machine. When presented with a system spec they will rapidly jump from problems to solutions, accepting and rejecting numerous ideas in rapid succession before arriving at a proposal. They will ask detailed questions and will adapt their model and proposed solution on the fly, with little to no actual conscious thought. The ideas just appear to them. E.g. they'll read the spec for a new auth service with required custom features and will reject building it from scratch and will instead propose an off-the-shelf solution wrapped by another service that adds the missing features (assumes this is the optimal solution for the problem, it's made up example after all).

Expert engineers are rare; they may be considered a "principle" in most orgs. You'll probably only work with a handful of them in your career. This isn't surprising, as the wealth of experience needed to reach this level is vast and takes conscious effort.

They are excellent communicators, but ironically, they may struggle to explain why they landed at the solution that they did. So much of their thinking is background and it takes a bit of conscious effort to work turn their intuition back into rules and principles. This is why experts are not great teachers of beginners, they are so many levels above that their even their reverse engineered rules will be too high level and big picture for someone that's just getting a handle of the basics. They are also both confident and humble, a key difference to expert beginners.

Their big picture is the big picture of the business itself. They understand the needs and how to meet those needs with a long-term perspective.

Enabling these devs is simple. Define the boundaries of their responsibility and let them have at it, give them a lot of flexibility and let them lead. Experts will spot problems that leadership hasn't, and will bring proposed solutions to the table with a list of tradeoffs. Work with them to prioritise but give them freedom, as they will succeed and so will the business.

Feedback loops are all about letting them try new things. They have a lot of intuitive systems, so any new technology will rapidly become incorporated into their thinking and decision-making. Having others at their level to iterate with can speed things up, but it might be difficult to find them.

6. Master:

Masters change the game. A master of software development will reject some "rules" and explore new paths, discovering new opportunities and techniques.

Most of us will never work with a master; they're so rare. Funnilly enough they don't even take lofty titles, often simply calling themselves "software engineers".

An example of a master is Eric Evans, the creator and author of Domain-Driven Design. Eric challenged the dominant paradigm of data-model-driven development, which had a focus on technology and data models. This development style viewed software dev as complicated and procedural, taking in business needs and directly translating them into data structures and technical concepts. It doesn't factor in the change inherent in the business and eventually leads to brittle software that resists change.

Instead, Eric flipped the script by putting the business needs and processes first. Technology and table structures are viewed as implementation details and of secondary importance. This led to a shift in software development, making the complexity of the business's domain and language a core part of the conversation and resulting software, leading to streamlined conversation (no translation, we're using the same terms) and systems that meet current needs and can adapt for future ones.

Another example is Kent Beck and his creation, extreme programming. The paradigm at the time was lots of upfront planning, long dev cycles with quarterly releases. Kent challenged this and thought, "What if we went faster, releasing small chunks quickly and learned as we go?". He went hell for leather, pushing these ideas to the extreme (thus the name) and discovered the resulting software was actually better. This philosophy is now a core tenet of agile and has changed the way we work.

Both of these are big shifts and ones that are only possible when a master thinks "Hmmm, this isn't working" and then lets their intuition guide them to new ways of doing things. Me, I'm not there yet, but give me another decade, maybe two, and we'll see.

Group learning

Up until now I've only discussed how this model works one-to-one, but what about in a group? This one is tricky; you'll never have a session where everyone learns the same thing or gets the same benefit, as we're all at different levels of abstraction, but an optimal balance is possible. First off, you need to figure out the base level. If the goal is to upskill a group at that level, then you need to factor in the appropriate big picture. This does mean that higher level devs won't learn as much, but there is an opportunity here. Higher-level devs can become facilitators, helping those at lower levels to progress, letting the higher-level devs practice the skill of communication and mentoring while the lower-level devs explore the idea in a way that's practical and actionable. (There's so much more to potentially write here, but I gotta stop somewhere, hit me up online or in the comments if you'd like to discuss this more)

Conclusion

So that was a lot, though now I hope you can see the value of the framework. It's not perfect; people don't reach these levels uniformly, but as a way of thinking through where a dev is at and how to move them forward, it is invaluable.

The short version is to figure out where a developer is within the spectrum of your org or speciality, then define the skills they have and what skills and experience they need to progress to the next level. Start concrete and work your way to abstract, aiming to give them the knowledge and experience they need to build up their mental models and turn them from conscious thought processes into unconscious ones.

And now for the mandatory engagement closer. Did you find this useful? Have you used the Dreyfus Skills model yourself and have differing thoughts? Are you mad about something online and want to make the conversation about that instead? If so, please leave a comment below or send me a message on Bluesky!